Table of Contents

- 1. Focusing on Contribution versus Focusing on Entitlement

- 2. Focusing on Outcome versus Focusing on Output

- 3. Sorting for What’s Needed versus What’s Requested

- 4. Work Yourself Out of a Job—Don’t Work to Protect Your Job

- 5. Go Toward Big Decisions, Even Without Authority

- 6. See Your Circumstances as Illusory and Temporary, Not Real and Permanent

What is the main difference between self-educated people—who enjoy massive success in their lives—and the majority of other people, who are wondering how to bring more success, happiness, and achievement into their lives?

It all boils down to one thing. They’ve chosen to do whatever it takes to create the lives that they want, including exercising the effort and initiative to figure out what “whatever it takes” is. What they didn’t do is sit around, waiting for someone else to feed them the answer, give them the right opportunity, make things safe or easy for them, or give them permission or authorization or the right credentials to get started figuring what needs to get done, and getting it done. (Excerpt is inspired from “The Education of Millionaires” by Michael Ellsberg).

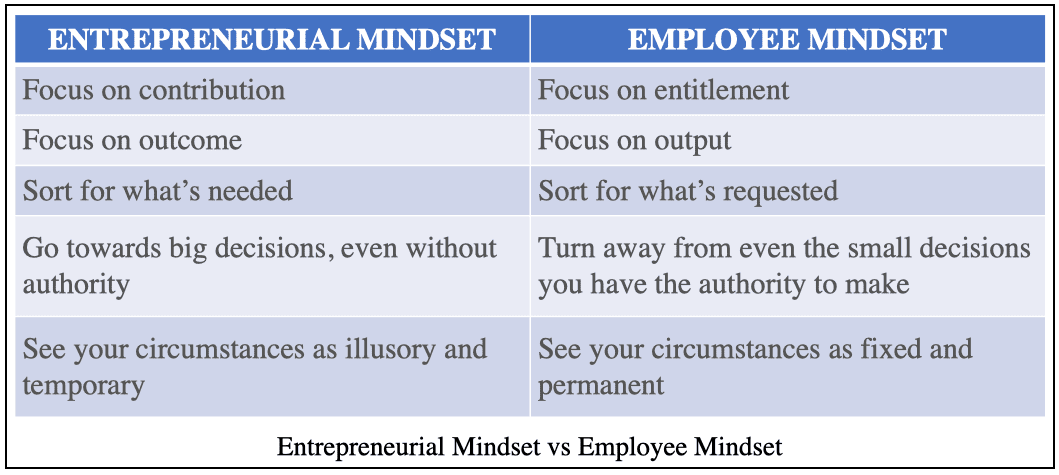

Bryan Franklin and his partner in business and life Jennifer Russell have called this shift—toward taking your success into your own hands—“The Entrepreneurial Mindset versus the Employee mindset.” This mindset shift is the single key distinction that separates self-made success—from passivity, feelings of victimization, and helplessness. Keep in mind, this distinction has nothing to do with whether you’re actually an entrepreneur or an employee. It’s about mindset. Many employees display the entrepreneurial mindset (they’re usually the ones who get promoted and promoted again and again), and many entrepreneurs display the employee mindset (they’re the ones who typically go out of business).

The entrepreneurial mindset, according to Bryan and Jennifer (who codeveloped this concept), involves six key distinctions. It is, perhaps, the DNA of career success.

If you want to be an entrepreneur, these distinctions contain the key tools for creating your own entrepreneurial success. Suppose you want to have a kick-ass career in a corporation as an employee. In that case, these distinctions contain the key tools for distinguishing yourself from the cubicle herd and getting on the radar of people who make promotions and look for leadership talent in your organization, fast.

1. Focusing on Contribution versus Focusing on Entitlement

Focusing your life around contribution means paying great attention to what you can contribute to any given person or situation you care about. It’s the “give, give, give” philosophy.

Anything you believe you can count on to be there, without regard for what you yourself are doing to ensure it’s there—that’s entitlement. When you lose a job or a client, do you have the sense that you lost something that you had? (That’s entitlement.) Or, do you immediately think, ‘Wow, I needed to contribute more there. How can I contribute more in the future? (That’s contribution.)

“The attitude, that you’re entitled to a job, even a promotion, no matter what results you produce there, is a death sentence for doing the kinds of things that actually lead to you getting promoted and becoming indispensable in the organization; it is itself a leading risk factor in getting laid off.”

2. Focusing on Outcome versus Focusing on Output

The successful people engaged in deep inquiry about what outcomes they specifically wanted to create in their lives, and then relentlessly engaged in only the activities directly related to producing those outcomes in their lives.

Self-educated serial entrepreneur Scott Banister, who sold his IronPort Web security appliance company to Cisco in 2007 for $830 million, is a living example of focusing on the outcome instead of output. Scott was studying at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in the late nineties, with the intention of becoming a professor of computer science. On the side of his studies, he began teaching himself HTML (hypertext markup language). He soon applied for and got a job as a webmaster, and then started various Web companies, including a banner ad company with college buddy Max Levchin (who later went on to co-found PayPal).

“We tell kids school is important, and most kids, including myself, believe that, and keep going further and further into formal education, with the attitude that ‘this is what’s important in the world.’

Well, the problem with that is that that’s just a cliff that just ends at some point. It’s like ‘Do well in school! Do well in school! Do well in school!’ And then, once you’re out, you realize: oops, actually, this is not how the world works, you don’t earn any money directly from doing well in school, and you can’t even support yourself! It’s a road that might go somewhere, but it might not. For a lot of people, that’s a really disappointing thing. They dutifully go through the process, and they finish high school, and they go to college, and they finish college, and they’re like, ‘Great, where’s my red carpet to financial security!’”

All the way up through college, we assume we’re learning a vocation, separate from business, such as being a doctor, or a lawyer, or an engineer, or a nurse, or a computer programmer. Then, alongside all these vocations, there’s this other vocation over here called ‘business.’ And that’s for some small number of people, who go learn about ‘business.’ And the rest of us will become doctors, lawyers, engineers, nurses, and computer programmers. The reality is, no matter what vocation you’re in, you end up working for a business of one kind or another. Thus, everyone’s vocation is business. No matter what you’re doing, your vocation is business. The more you can understand the machinery that you’re working in, the better off you’re going to be.”

Those in the employee mindset, in turn, feel satisfied if they just work harder and harder and harder—in school, at a workplace, or in a business—without paying much attention to whether all that effort is directly producing the specific outcomes they want. In many ways, our modern school-to-workplace system was specifically designed to be populated with people exhibiting the employee mindset of turning out more and more output without focusing on real-world outcomes.

If you want real financial security—run always toward creating real-world results for people who are willing to pay for these results, and you’ll never have to worry about money; it will always be there for you in sufficient supply. The entrepreneurial mindset, which involves focusing on the outcome rather than output and contribution rather than entitlement, applied in your own ongoing self-education, your own business, or your place of work, is the recipe.

3. Sorting for What’s Needed versus What’s Requested

If you look for and take care of what’s needed in a situation, rather than what’s requested by your boss, your teammates, or your clients, you’ll always be the first one up for promotions, the first one to win new business, and the last one laid off.

Multi-entrepreneur Russell Simmons told Michael Ellsberg, “Find out what people in your organization need and give them that service. That is the way entrepreneurs think—‘I’m going to fix the problem.’ You get paid by how many problems you solve, and people will gravitate toward you. If you know your boss’s job better than your boss, your boss is going to count on you for more things. You can begin to learn different parts of the job more than the boss knows them—you can’t start anywhere, it doesn’t make a difference. The person who can start solving problems and exercising initiative and leadership at the bottom certainly won’t be able to at the top, either—and in fact, that person won’t even get to the top.”

The late Wharton management professor Russell Ackoff writes, “Every child learns at a very early stage that when they’re asked a question in school they must first ask themselves a question: What answer does the asker expect? That’s the way you get through school, by providing people with the answers they expect. Now, one thing about an answer that somebody else expects is it can’t be creative because it’s already known. What we ought to be trying to do with children is get them to give us answers that we don’t expect—to stimulate creativity. We kill it in school.”

Sadly, our education system, in its current form, is essentially one long series of artificial classroom situations in which the purpose is essentially to do what has been requested by an authority figure. This is the opposite of how success occurs in the real world.

4. Work Yourself Out of a Job—Don’t Work to Protect Your Job

What’s the best way to ensure you never climb to the next rung on the ladder in your workplace or business? By adhering desperately to the lower rung as if it were your salvation in life.

How do you become a leader in your workplace or your business? By making yourself obsolete in your current role and finding a higher-leverage role to play. And then making yourself obsolete in that and finding a higher-leverage role to play. And on and on.

Celebrated business author Guy Kawasaki—who holds an undergraduate degree from Stanford and an MBA from UCLA—expresses this sentiment clearly in the New York Times: “the ideal goal would be to make yourself dispensable—what greater accomplishment is there than the organization running well without you? It means you picked great people, prepared them, and inspired them. And if executives did this, the world would be a better place.”

Actually, someone who continuously makes themselves “dispensable” and “redundant” at their lower-leverage roles in the organization—through good hiring, outsourcing, delegation, automation, systematization, whatever—and at the same time continuously seeks roles of greater and greater leverage and leadership, is indispensable to the organization.

5. Go Toward Big Decisions, Even Without Authority

Successful people didn’t wait around for someone to tell them to be successful. They didn’t wait around for someone to tell them they could make big decisions in their lives, and have a big impact.

Could there be anything more audacious than agreeing to have a big impact on society, without jumping through all the hoops and checking off all the checkmarks society tells you that you need to check off before you can do so?

Bryan Franklin explains: “If I work in a retail store, and I don’t have any training, tools, power, or budget, and I believe I can make a positive impact on sales, I’m going to start just making those decisions. I don’t need the authority. I’m trying to make a contribution and have the outcome be good for the store. I might make a mistake, and I’ll accept the consequences, but any smart boss will see that my intentions are to make him more money and will soon start to see me as an indispensable employee, ready for promotion.

People with an employee mindset don’t want to be the one responsible for making a bad decision, so they move away from responsibility for all decisions. It’s part of protecting their job. But they didn’t get the message that, in this economy, such behavior is the opposite of ensuring your future employment. Because they’re not making any real decisions, which means they’re not having any real impact. They’ll be the first to go when leaders start looking to trim fat.”

6. See Your Circumstances as Illusory and Temporary, Not Real and Permanent

This last point might risk getting too philosophical for some readers. But I think it’s important.

A key aspect of the entrepreneurial mindset is seeing the world around you as largely made up. Sure, there are societal rules, but those rules are often arbitrary and outdated, and can therefore frequently be broken, bent, bypassed, or just plain ignored, to good effect.

People with an entrepreneurial mindset, look out at the world and see malleability, elasticity, plasticity, and flexibility. They see how they can bend the currently accepted “reality” toward the reality they would prefer.

Those with the employee mindset, in turn, look out and see a world full of protocols, rules, regulations, fixed hierarchies, and established orders. They bow their head down and “stick with the program,” hoping that if they just do what they’re told and what’s expected of them, it will turn out all right, just as Mom or Dad or Teacher or Professor or Boss said it would.

There’s more wiggle room and more flexibility at the joints of society than you might have imagined. You just have to look for it. This is the essence of the entrepreneurial mindset.

“A reasonable man adapts himself to his environment,” George Bernard Shaw tells us. “An unreasonable man persists in attempting to adapt his environment to suit himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

So, do you have an employee mindset or an entrepreneurial mindset?